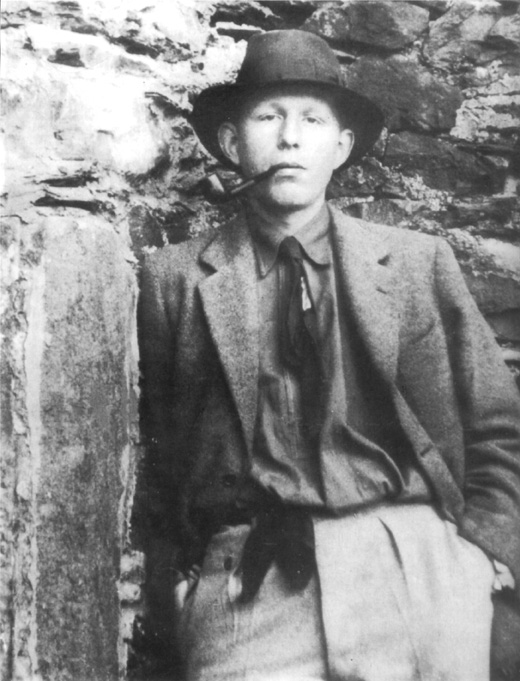

My friend and mentor David Mycoff died in December. He was brilliant, and so were his colleagues in the Warren Wilson College English Department. I tried to explain once what made me think this, but I could not get hold of something outside of the experience of being taught by each one of them that could service as a reference point for someone who did not share that experience. Between them, however, it seemed clear that they knew and respected each others’ scholarship and approach to teaching.

What they all seemed to share was a bent toward the curmudgeonly. At gatherings of department faculty and students, one professor could be prevailed upon to read the Hermetic Decalogue from W.H. Auden’s Upon Which Lyre, starting with the stanza

Thou shalt not do as the dean pleases,

Thou shalt not write thy doctor’s thesis

On education,

Thou shalt not worship projects nor

Shalt thou or thine bow down before

Administration.

The whole poem is worth reading. It was written in 1946 for the Harvard chapter of Phi Beta Kappa and subtitled “A Reactionary Tract For The Times”. From what I can gather, Auden was warning his audience about the nascent movement to make academia “relevant.”

By the time Mycoff retired, the last of his battalion to surrender the field, the concern for relevance had transmuted into a calculation of “impact.” How does the college impact students? How do students impact the world? By what metric can we measure such impact? All of this, I suppose, is a greater manifestation of the same attempt I had made earlier to peg my experience on to a wider reference point.

What that assumes, of course, is the reference point is stable, that it makes sense, that it is a standard worth measuring against. The reference point that higher education seems to have settled upon is, oddly, employment. That one goes to college in order to get a job is a truism that goes almost unquestioned by anyone. What students ask instead is whether or not they should go to college if they have no earthly idea who they are or what they want to do. In some cases, the pressure to define that as quickly as possible so that a college or university can be maximumly impactful drives students out of the classroom.

The classroom, however, ought to be exactly the place to explore such questions. That they are not allowed to be is the direct result of artificial pressure placed on colleges and universities to document their usefulness to the wider world. Here’s what’s so nefarious in that situation: the academy exists to scrutinize, to evaluate the wider world, not to be evaluated by it. As tensions have increased between, say, climate scientists and the petrochemical industry, or cultural demagogues and historians, administrations have buckled under the pressure of the demands of the wider world rather than preserving the prerogative of the academy to question the premises of those demands. This has not played out well for Higher Ed.

That is why I suspect my friend and mentor, the son and brother of Episcopal clergy, would give the eyeroll to end all eyerolls to the most recent “Report Of Episcopal Congregations And Missions According To Canons I.6, I.7, And I.17 (Otherwise Known As The Parochial Report)”, the first section of which has been revised from previous years to calculate “Total Attendance and Impact.” The first quarter of the eyeroll might be devoted to the idea that numbers — number of people attending a service, number of people viewing a service online, number of people participating in mission work, number of people being served by mission work — that these numbers bear any relation to who has or has not been transformed by the redeeming power of the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

The remainder of the eyeroll very well should be devoted to the proposition that there is some audience somewhere that can or should be awed, swayed, or otherwise persuaded by any sort of metric measuring a church’s impact. What surely follows is a discussion about how much impact is enough (or even too much). The beast that devoured higher education could not but turn its head this way to gobble up yet another institution that exists, at least in part, to evaluate the existence and behavior of the beast. Why should the wider world be subjected to the critical scrutiny of the church if the world can simply turn the church back onto itself?

All of this is corollary to question of what in the hell impact is supposed to mean. Is the world a static field into which we hurl the church, hoping to pierce and disrupt without any notion of what comes next? Do we see people as passive receptors of a message so good and true that we have to hurl it at them, hoping it will implant itself somewhere in their psyche? If that strategy works, is their utility solely as a unit of measurement? I don’t honestly think that is the intention of the Parochial Report, but that is the same — or at least similar — road to the one higher education took on its journey toward commoditizing students.

So what, I ask myself, would David Mycoff do? Try to understand the problem clearly might be the first step. Hence this little essay. I think he also would look for the places in which he could substitute metrics for relationships. Someone, somewhere can try to make use of the numbers on the page, but while the student, the parishioner, the person hungry for hope stands before us, we can serve them and the image of God that is within them. If the institution may be eroding around us, the urgency of the moment is to be in relationship with the person next to us, as fully as we can, right now.

Auden’s Hermetic Decalogue ends with the command:

In that spirit, here’s a series of quotes from an article in the March 10, 2025 edition of the New Yorker entitled “ Annals of Higher Education: As Harvard Goes”

– “Universities have already begun to shift how they justify their existence,” Clune went on. “It’s away from the traditional, you know, ‘pursuit of knowledge’ and toward the stuff you read on corporate Web sites—like, we’re here to ‘create value’ and ‘create engaging customer experiences.’”

– Lessin told me he shares a widespread donor view that, at a moment when universities have become large and growth-oriented, more like companies, scholars are the wrong people to guide their trajectories. “The wild card is the faculty—they’re by far the hardest thing to solve for,” he said. “The students change every four years, so you can make a mistake, put the wrong people in, select for the wrong things, and fix it.” Scholars were often there for life, and held misguided sway. “The faculty is a unique characteristic of universities versus companies,” he noted. “It’s not clear what to do about it.”

– Of the eight Ivy League presidents, five rose to high administration from professional schools, and four have a medical background. All this has left many faculty members feeling beside the point, especially in pursuits like chemistry, classics, English, government, or law—five scholarly fields that together produced every Harvard president of the twentieth century. Undergraduates are said to have ever more pre-professional orientations at the expense of the liberal arts; one professor ruefully described the place as the world’s most élite trade school.

– “If you were to ask many of our colleagues, they would put the blame on students,” Masoud said. “They would say that our students are incapable of ‘absorbing’ or ‘coping with’ views that they object to, which they then label as offensive and harmful.” He thought that this was an idea to which a vulnerable and anxious leadership was overly attached. The university made a show of rolling out “candid and constructive conversation” programs, but Masoud saw an increasingly public, corporatized institution imposing its own anxieties on young minds.

– He reflected for a moment, then continued. “The message should be: Look. We are a university,” he said.

The message should be “Look, we are a church.”